Concerts, sporting matches and games, and political rallies can have very large crowds. When you attend one of these events you may know only the people you came with, yet you may experience a feeling of connection to the group. You are one of the crowd. You cheer and applaud when everyone else does. You boo and yell alongside them. You move out of the way when someone needs to get by, and you say “excuse me” when you need to leave. You know how to behave in this kind of crowd.

It can be a very different experience if you are travelling in a foreign country and you find yourself in a crowd moving down the street. You may have trouble figuring out what is happening. Is the crowd just the usual morning rush, or is it a political protest of some kind? Perhaps there was some sort of accident or disaster. Is it safe in this crowd, or should you try to extract yourself? How can you find out what is going on? Although you are in it, you may not feel like you are part of this crowd. You may not know what to do or how to behave.

Even within one type of crowd, different groups exist and different behaviours are on display. At a rock concert, for example, some may enjoy singing along, others may prefer to sit and observe, while still others may join in a mosh pit or try crowd-surfing. On February 28, 2010, Sydney Crosby scored the winning goal against the United States team in the gold medal hockey game at the Vancouver Winter Olympics. Two hundred thousand jubilant people filled the streets of downtown Vancouver to celebrate and cap off two weeks of uncharacteristically vibrant, joyful street life in Vancouver. Just over a year later, on June 15, 2011, the Vancouver Canucks lost the seventh hockey game of the Stanley Cup finals against the Boston Bruins. One hundred thousand people had been watching the game on outdoor screens. Eventually 155,000 people filled the downtown streets. Rioting and looting led to hundreds of injuries, burnt cars, trashed storefronts and property damage totaling an estimated $4.2 million. Why was the crowd response to the two events so different?

A key insight of sociology is that the simple fact of being in a group changes your behaviour. The group is a phenomenon that is more than the sum of its parts. Why do we feel and act differently in different types of social situations? Why might people of a single group exhibit different behaviours in the same situation? Why might people acting similarly not feel connected to others exhibiting the same behaviour? These are some of the many questions sociologists ask as they study people and societies.

A dictionary defines sociology as the systematic study of society and social interaction. The word “sociology” is derived from the Latin word socius (companion) and the Greek word logos (speech or reason), which together mean “reasoned speech or discourse about companionship”. How can the experience of companionship or togetherness be put into words or explained? While this is a starting point for the discipline, sociology is actually much more complex. It uses many different theories and methods to study a wide range of subject matter, and applies these studies to the real world.

The sociologist Dorothy Smith (b. 1926) defines the social as the “ongoing concerting and coordinating of individuals’ activities” (Smith, 1999). Sociology is the systematic study of all those aspects of life designated by the adjective “social.” They concern relationships, and they concern what happens when more than one person is involved. These aspects of social life never simply occur; they are organized processes. They can be the briefest of everyday interactions — moving to the right to let someone pass on a busy sidewalk, for example — or the largest and most enduring interactions — such as the billions of daily exchanges that constitute the circuits of global capitalism. If there are at least two people involved, even in the seclusion of one’s mind, then there is a social interaction that entails the “ongoing concerting and coordinating of activities.” Why does the person move to the right on the sidewalk? What collective processes lead to the decision that moving to the right rather than the left is normal? Think about the T-shirts in your chest of drawers at home. What are the sequences of linkages, exchanges, and social relationships that connect your T-shirts to the dangerous and hyper-exploitative garment factories in rural China or Bangladesh? These are the type of questions that point to the unique domain and puzzles of the social that sociology seeks to explore and understand.

Sociologists study all aspects and levels of society. A society is a group of people whose members interact, reside in a definable area, and share a culture. A culture includes the group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, norms, and artifacts. One sociologist might analyze video of people from different societies as they carry on everyday conversations to study the rules of polite conversation from different world cultures. Another sociologist might interview a representative sample of people to see how email and instant messaging have changed the way organizations are run. Yet another sociologist might study how migration determined the way in which language spread and changed over time. A fourth sociologist might study the history of international agencies like the United Nations or the International Monetary Fund to examine how the globe became divided into a First World and a Third World after the end of the colonial era.

These examples illustrate the ways in which society and culture can be studied at different levels of analysis, from the detailed study of face-to-face interactions to the examination of large-scale historical processes affecting entire civilizations. It is common to divide these levels of analysis into different gradations based on the scale of interaction involved. As discussed in later chapters, sociologists break the study of society down into four separate levels of analysis: micro, meso, macro, and global. The basic distinctions, however, are between micro-level sociology, macro-level sociology and global-level sociology.

The study of cultural rules of politeness in conversation is an example of micro-level sociology. At the micro-level of analysis, the focus is on the social dynamics of intimate, face-to-face interactions. Research is conducted with a specific set of individuals such as conversational partners, family members, work associates, or friendship groups. In the conversation study example, sociologists might try to determine how people from different cultures interpret each others’ behaviour to see how different rules of politeness lead to misunderstandings. If the same misunderstandings occur consistently in a number of different interactions, the sociologists may be able to propose some generalizations about rules of politeness that would be helpful in reducing tensions in mixed-group dynamics (e.g., during staff meetings or international negotiations). Other examples of micro-level research include seeing how informal networks become a key source of support and advancement in formal bureaucracies, or how loyalty to criminal gangs is established.

Macro-level sociology focuses on the properties of large-scale, society-wide social interactions that extend beyond the immediate milieu of individual interactions: the dynamics of institutions, class structures, gender relations, or whole populations. The example above of the influence of migration on changing patterns of language usage is a macro-level phenomenon because it refers to structures or processes of social interaction that occur outside or beyond the intimate circle of individual social acquaintances. These include the economic, political, and other circumstances that lead to migration; the educational, media, and other communication structures that help or hinder the spread of speech patterns; the class, racial, or ethnic divisions that create different slangs or cultures of language use; the relative isolation or integration of different communities within a population; and so on. Other examples of macro-level research include examining why women are far less likely than men to reach positions of power in society, or why fundamentalist Christian religious movements play a more prominent role in American politics than they do in Canadian politics. In each case, the site of the analysis shifts away from the nuances and detail of micro-level interpersonal life to the broader, macro-level systematic patterns that structure social change and social cohesion in society.

In global-level sociology, the focus is on structures and processes that extend beyond the boundaries of states or specific societies. As Ulrich Beck (2000) has pointed out, in many respects we no longer “live and act in the self-enclosed spaces of national states and their respective national societies.” Issues of climate change, the introduction of new technologies, the investment and disinvestment of capital, the images of popular culture, or the tensions of cross-cultural conflict, etc. increasingly involve our daily life in the affairs of the entire globe, by-passing traditional borders and, to some degree, distance itself. The example above of the way in which the world became divided into wealthy First World and impoverished Third World societies reflects social processes — the formation of international institutions such as the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and non-governmental organizations, for example — which are global in scale and global in their effects. With the boom and bust of petroleum or other export commodity economies, it is clear to someone living in Fort McMurray, Alberta, that their daily life is affected not only by their intimate relationships with the people around them, nor only by provincial and national based corporations and policies, etc., but by global markets that determine the price of oil and the global flows of capital investment. The context of these processes has to be analysed at a global scale of analysis.

The relationship between the micro, macro, and global remains one of the key conceptual problems confronting sociology. What is the relationship between an individual’s life and social life? The early German sociologist Georg Simmel pointed out that macro-level processes are in fact nothing more than the sum of all the unique interactions between specific individuals at any one time (1908/1971), yet they have properties of their own which would be missed if sociologists only focused on the interactions of specific individuals. Émile Durkheim’s classic study of suicide (1897/1951) is a case in point. While suicide is one of the most personal, individual, and intimate acts imaginable, Durkheim demonstrated that rates of suicide differed between religious communities — Protestants, Catholics, and Jews — in a way that could not be explained by the individual factors involved in each specific case. The different rates of suicide had to be explained by macro-level variables associated with the different religious beliefs and practices of the faith communities; more specifically, the different degrees of social integration of these communities. We will return to this example in more detail later. On the other hand, macro-level phenomena like class structures, institutional organizations, legal systems, gender stereotypes, population growth, and urban ways of life provide the shared context for everyday life but do not explain its specific nuances and micro-variations very well. Macro-level structures constrain the daily interactions of the intimate circles in which we move, but they are also filtered through localized perceptions and “lived” in a myriad of inventive and unpredictable ways.

Although the scale of sociological studies and the methods of carrying them out are different, the sociologists involved in them all have something in common. Each of them looks at society using what pioneer sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916-1962) called the sociological imagination, sometimes also referred to as the “sociological lens” or “sociological perspective.” In a sense, this was Mills’ way of addressing the dilemmas of the macro/micro divide in sociology. Mills defined sociological imagination as how individuals understand their own and others’ lives in relation to history and social structure (1959/2000). It is the capacity to see an individual’s private troubles in the context of the broader social processes that structure them. This enables the sociologist to examine what Mills called “personal troubles of milieu” as “public issues of social structure,” and vice versa.

Mills reasoned that private troubles like being overweight, being unemployed, having marital difficulties, or feeling purposeless or depressed can be purely personal in nature. It is possible for them to be addressed and understood in terms of personal, psychological, or moral attributes — either one’s own or those of the people in one’s immediate milieu. In an individualistic society like our own, this is in fact the most likely way that people will regard the issues they confront: “I have an addictive personality;” “I can’t get a break in the job market;” “My husband is unsupportive,” etc. However, if private troubles are widely shared with others, they indicate that there is a common social problem that has its source in the way social life is structured. At this level, the issues are not adequately understood as simply private troubles. They are best addressed as public issues that require a collective response to resolve.

Obesity, for example, has been increasingly recognized as a growing problem for both children and adults in North America. Michael Pollan cites statistics that three out of five Americans are overweight and one out of five is obese (2006). In Canada in 2012, just under one in five adults (18.4%) were obese, up from 16% of men and 14.5% of women in 2003 (Statistics Canada, 2013). Obesity is therefore not simply a private concern related to the medical issues, dietary practices, or exercise habits of specific individuals. It is a widely shared social issue that puts people at risk for chronic diseases like hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. It also creates significant social costs for the medical system.

Pollan argues that obesity is in part a product of the increasingly sedentary and stressful lifestyle of modern, capitalist society. More importantly, however, it is a product of the industrialization of the food chain, which since the 1970s has produced increasingly cheap and abundant food with significantly more calories due to processing. Additives like corn syrup, which are much cheaper and therefore more profitable to produce than natural sugars, led to the trend of super-sized fast foods and soft drinks in the 1980s. As Pollan argues, trying to find a processed food in the supermarket without a cheap, calorie-rich, corn-based additive is a challenge. The sociological imagination in this example is the capacity to see the private troubles and attitudes associated with being overweight as an issue of how the industrialization of the food chain has altered the human/environment relationship — in particular, with respect to the types of food we eat and the way we eat them.

By looking at individuals and societies and how they interact through this lens, sociologists are able to examine what influences behaviour, attitudes, and culture. By applying systematic and scientific methods to this process, they try to do so without letting their own biases and preconceived ideas influence their conclusions.

All sociologists are interested in the experiences of individuals and how those experiences are shaped by interactions with social groups and society as a whole. To a sociologist, the personal decisions an individual makes do not exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns and social forces put pressure on people to select one choice over another. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behaviour of large groups of people living in the same society and experiencing the same societal pressures. When general patterns persist through time and become habitual or routinized at micro-levels of interaction, or institutionalized at macro or global levels of interaction, they are referred to as social structures.

As we noted above, understanding the relationship between the individual and society is one of the most difficult sociological problems. Partly this is because of the reified way these two terms are used in everyday speech. Reification refers to the way in which abstract concepts, complex processes, or mutable social relationships come to be thought of as “things.” A prime example of reification is when people say that “society” caused an individual to do something, or to turn out in a particular way. In writing essays, first-year sociology students sometimes refer to “society” as a cause of social behaviour or as an entity with independent agency. On the other hand, the “individual” is a being that seems solid, tangible, and independent of anything going on outside of the skin sack that contains its essence. This conventional distinction between society and the individual is a product of reification, as both society and the individual appear as independent objects. A concept of “the individual” and a concept of “society” have been given the status of real, substantial, independent objects. As we will see in the chapters to come, society and the individual are neither objects, nor are they independent of one another. An “individual” is inconceivable without the relationships to others that define their internal, subjective life and their external, socially-defined roles.

One problem for sociologists is that these concepts of the individual and society, and the relationship between them, are thought of in terms established by a very common moral framework in modern democratic societies — namely, that of individual responsibility and individual choice. The individual is morally responsible for their behaviours and decisions. Often in this framework, any suggestion that an individual’s behaviour needs to be understood in terms of that person’s social context is dismissed as “letting the individual off” for taking personal responsibility for their actions. Talking about society is akin to being morally soft or lenient.

Sociology, as a social science, remains neutral on these types of moral questions. For sociologists, the conceptualization of the individual and society is much more complex than the moral framework suggests and needs to be examined through evidence-based, rather than morality-based, research. The sociological problem is to be able to see the individual as a thoroughly social being and, yet, as a being who has agency and free choice. Individuals are beings who do take on individual responsibilities in their everyday social roles, and risk social consequences when they fail to live up to them. However, the manner in which individuals take on responsibilities, and sometimes the compulsion to do so, are socially defined. The sociological problem is to be able to see society as: a dimension of experience characterized by regular and predictable patterns of behaviour that exist independently of any specific individual’s desires or self-understanding. At the same time, a society is nothing but the ongoing social relationships and activities of specific individuals.

A key basis of the sociological perspective is the concept that the individual and society are inseparable. It is impossible to study one without the other. German sociologist Norbert Elias (1887-1990) called the process of simultaneously analyzing the behaviour of individuals and the society that shapes that behaviour figuration. He described it through a metaphor of dancing. There can be no dance without the dancers, but there can be no dancers without the dance. Without the dancers, a dance is just an idea about motions in a choreographer’s head. Without a dance, there is just a group of people moving around a floor. Similarly, there is no society without the individuals that make it up, and there are also no individuals who are not affected by the society in which they live (Elias, 1978).

In 2010 the CBC program The Current aired a report about several young Aboriginal men who were serving time in prison in Saskatchewan for gang-related activities (CBC, 2010). They all expressed desires to be able to deal with their drug addiction issues, return to their families, and assume their responsibilities when their sentences were complete. They wanted to have their own places with nice things in them. However, according to the CBC report, 80% of the prison population in the Saskatchewan Correctional Centre were Aboriginal and 20% of those were gang members. This is consistent with national statistics on Aboriginal incarceration which showed that in 2010–2011, the Aboriginal incarceration rate was 10 times higher than for the non-Aboriginal population. While Aboriginal people account for about 4% of the Canadian population, in 2013 they made up 23.2% of the federal penitentiary population. In 2001 they made up only 17% of the penitentiary population. Aboriginal overrepresentation in prisons has continued to grow substantially (Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2013). The outcomes of Aboriginal incarceration are also bleak. The federal Office of the Correctional Investigator summarized the situation as follows. Aboriginal inmates are:

The federal report notes that “the high rate of incarceration for Aboriginal peoples has been linked to systemic discrimination and attitudes based on racial or cultural prejudice, as well as economic and social disadvantage, substance abuse, and intergenerational loss, violence and trauma” (2013).

This is clearly a case in which the situation of the incarcerated inmates interviewed on the CBC program has been structured by historical social patterns and power relationships that confront Aboriginal people in Canada generally. How do we understand it at the individual level, however — at the level of personal decision making and individual responsibilities? One young inmate described how, at the age of 13, he began to hang around with his cousins who were part of a gang. He had not grown up with “the best life”; he had family members suffering from addiction issues and traumas. The appeal of what appeared as a fast and exciting lifestyle — the sense of freedom and of being able to make one’s own life, instead of enduring poverty — was compelling. He began to earn money by “running dope” but also began to develop addictions. He was expelled from school for recruiting gang members. The only job he ever had was selling drugs. The circumstances in which he and the other inmates had entered the gang life, and the difficulties getting out of it they knew awaited them when they left prison, reflect a set of decision-making parameters fundamentally different than those facing most non-Aboriginal people in Canada.

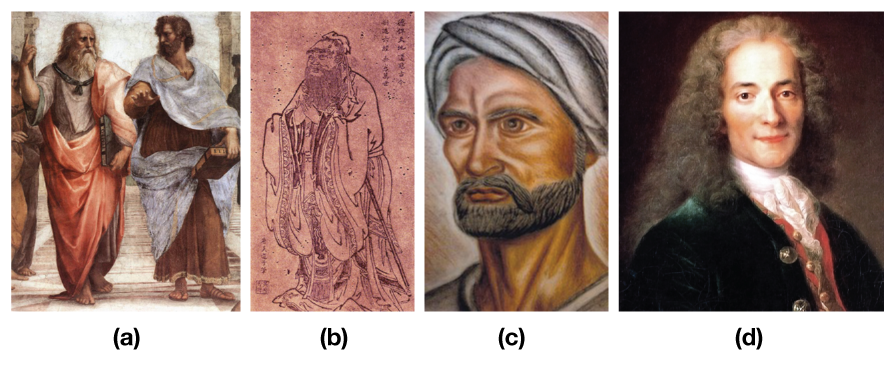

Since ancient times, people have been fascinated by the relationship between individuals and the societies to which they belong. The ancient Greeks might be said to have provided the foundations of sociology through the distinction they drew between physis (nature) and nomos (law or custom). Whereas nature or physis for the Greeks was “what emerges from itself” without human intervention, nomos in the form of laws or customs, were human conventions designed to constrain human behaviour. The modern sociological term “norm” (i.e., a social rule that regulates human behaviour) comes from the Greek term nomos. Histories by Herodotus (484–425 BCE) was a proto-anthropological work that described the great variations in the nomos of different ancient societies around the Mediterranean, indicating that human social life was not a product of nature but a product of human creation. If human social life was the product of an invariable human or biological nature, all cultures would be the same. The concerns of the later Greek philosophers — Socrates (469–399 BCE), Plato (428–347 BCE), and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) — with the ideal form of human community (the polis or city-state) can be derived from the ethical dilemmas of this difference between human nature and human norms. The ideal community might be rational but it was not natural.

In the 13th century, Ma Tuan-Lin, a Chinese historian, first recognized social dynamics as an underlying component of historical development in his seminal encyclopedia, General Study of Literary Remains. The study charted the historical development of Chinese state administration from antiquity in a manner very similar to contemporary institutional analyses. The next century saw the emergence of the historian some consider to be the world’s first sociologist, the Berber scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) of Tunisia. His Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History is known for going beyond descriptive history to an analysis of historical processes of change based on his insights into “the nature of things which are born of civilization” (Khaldun quoted in Becker and Barnes, 1961). Key to his analysis was the distinction between the sedentary life of cities and the nomadic life of pastoral peoples like the Bedouin and Berbers. The nomads, who exist independent of external authority, developed a social bond based on blood lineage and “esprit de corps” (‘Asabijja), which enabled them to mobilize quickly and act in a unified and concerted manner in response to the rugged circumstances of desert life. The sedentaries of the city entered into a different cycle in which esprit de corps is subsumed to institutional power and the intrigues of political factions. The need to be focused on subsistence is replaced by a trend toward increasing luxury, ease, and refinements of taste. The relationship between the two poles of existence, nomadism and sedentary life, was at the basis of the development and decay of civilizations (Becker and Barnes, 1961).

However, it was not until the 19th century that the basis of the modern discipline of sociology can be said to have been truly established. The impetus for the ideas that culminated in sociology can be found in the three major transformations that defined modern society and the culture of modernity: the development of modern science from the 16th century onward, the emergence of democratic forms of government with the American and French Revolutions (1775–1783 and 1789–1799 respectively), and the Industrial Revolution beginning in the 18th century. Not only was the framework for sociological knowledge established in these events, but also the initial motivation for creating a science of society. Early sociologists like Comte and Marx sought to formulate a rational, evidence-based response to the experience of massive social dislocation brought about by the transition from the European feudal era to capitalism. This was a period of unprecedented social problems, from the breakdown of local communities to the hyper-exploitation of industrial labourers. Whether the intention was to restore order to the chaotic disintegration of society, as in Comte’s case, or to provide the basis for a revolutionary transformation in Marx’s, a rational and scientifically comprehensive knowledge of society and its processes was required. It was in this context that “society” itself, in the modern sense of the word, became visible as a phenomenon to early investigators of the social condition.

The development of modern science provided the model of knowledge needed for sociology to move beyond earlier moral, philosophical, and religious types of reflection on the human condition. Key to the development of science was the technological mindset that Max Weber termed the disenchantment of the world: “principally there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather one can, in principle, master all things by calculation” (1919). The focus of knowledge shifted from intuiting the intentions of spirits and gods to systematically observing and testing the world of things through science and technology. Modern science abandoned the medieval view of the world in which God, “the unmoved mover,” defined the natural and social world as a changeless, cyclical creation ordered and given purpose by divine will. Instead modern science combined two philosophical traditions that had historically been at odds: Plato’s rationalism and Aristotle’s empiricism (Berman, 1981). Rationalism sought the laws that governed the truth of reason and ideas, and in the hands of early scientists like Galileo and Newton, found its highest form of expression in the logical formulations of mathematics. Empiricism sought to discover the laws of the operation of the world through the careful, methodical, and detailed observation of the world. The new scientific worldview therefore combined the clear and logically coherent, conceptual formulation of propositions from rationalism, with an empirical method of inquiry based on observation through the senses. Sociology adopted these core principles to emphasize that claims about social life had to be clearly formulated and based on evidence-based procedures. It also gave sociology a technological cast as a type of knowledge which could be used to solve social problems.

The emergence of democratic forms of government in the 18th century demonstrated that humans had the capacity to change the world. The rigid hierarchy of medieval society was not a God-given eternal order, but a human order that could be challenged and improved upon through human intervention. Through the revolutionary process of democratization, society came to be seen as both historical and the product of human endeavours. Age of Enlightenment philosophers like Locke, Voltaire, Montaigne, and Rousseau developed general principles that could be used to explain social life. Their emphasis shifted from the histories and exploits of the aristocracy to the life of ordinary people. Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) extended the critical analysis of her male Enlightenment contemporaries to the situation of women. Significantly for modern sociology they proposed that the use of reason could be applied to address social ills and to emancipate humanity from servitude. Wollstonecraft for example argued that simply allowing women to have a proper education would enable them to contribute to the improvement of society, especially through their influence on children. On the other hand, the bloody experience of the democratic revolutions, particularly the French Revolution, which resulted in the “Reign of Terror” and ultimately Napoleon’s attempt to subjugate Europe, also provided a cautionary tale for the early sociologists about the need for the sober scientific assessment of society to address social problems.

The Industrial Revolution in a strict sense refers to the development of industrial methods of production, the introduction of industrial machinery, and the organization of labour to serve new manufacturing systems. These economic changes emblemize the massive transformation of human life brought about by the creation of wage labour, capitalist competition, increased mobility, urbanization, individualism, and all the social problems they wrought: poverty, exploitation, dangerous working conditions, crime, filth, disease, and the loss of family and other traditional support networks, etc. It was a time of great social and political upheaval with the rise of empires that exposed many people — for the first time — to societies and cultures other than their own. Millions of people were moving into cities and many people were turning away from their traditional religious beliefs. Wars, strikes, revolts, and revolutionary actions were reactions to underlying social tensions that had never existed before and called for critical examination. August Comte in particular envisioned the new science of sociology as the antidote to conditions that he described as “moral anarchy.”

Sociology therefore emerged; firstly, as an extension of the new worldview of science; secondly, as a part of the Enlightenment project and its focus on historical change, social injustice, and the possibilities of social reform; and thirdly, as a crucial response to the new and unprecedented types of social problems that appeared in the 19th century with the Industrial Revolution. It did not emerge as a unified science, however, as its founders brought distinctly different perspectives to its early formulations.

The term sociology was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748–1836) in an unpublished manuscript (Fauré et al., 1999). In 1838, the term was reinvented by Auguste Comte (1798–1857). The contradictions of Comte’s life and the times he lived through can be in large part read into the concerns that led to his development of sociology. He was born in 1798, year 6 of the new French Republic, to staunch monarchist and Catholic parents. They lived comfortably off his father’s earnings as a minor bureaucrat in the tax office. Comte originally studied to be an engineer, but after rejecting his parents’ conservative, monarchist views, he declared himself a republican and free spirit at the age of 13 and was eventually kicked out of school at 18 for leading a school riot. This ended his chances of getting a formal education and a position as an academic or government official.

He became a secretary to the utopian socialist philosopher Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) until they had a falling out in 1824 (after St. Simon reputedly purloined some of Comte’s essays and signed his own name to them). Nevertheless, they both thought that society could be studied using the same scientific methods utilized in the natural sciences. Comte also believed in the potential of social scientists to work toward the betterment of society and coined the slogan “order and progress” to reconcile the opposing progressive and conservative factions that had divided the crisis-ridden, post-revolutionary French society. Comte proposed a renewed, organic spiritual order in which the authority of science would be the means to create a rational social order. Through science, each social strata would be reconciled with their place in a hierarchical social order. It is a testament to his influence in the 19th century that the phrase “order and progress” adorns the Brazilian coat of arms (Collins and Makowsky, 1989).

Comte named the scientific study of social patterns positivism. He described his philosophy in a well-attended and popular series of lectures, which he published as The Course in Positive Philosophy (1830–1842) and A General View of Positivism (1848/1977). He believed that using scientific methods to reveal the laws by which societies and individuals interact would usher in a new “positivist” age of history. In principle, positivism, or what Comte called “social physics,” proposed that the study of society could be conducted in the same way that the natural sciences approach the natural world.

While Comte never in fact conducted any social research, his notion of sociology as a positivist science that might effectively socially engineer a better society was deeply influential. Where his influence waned was a result of the way in which he became increasingly obsessive and hostile to all criticism as his ideas progressed beyond positivism as the “science of society” to positivism as the basis of a new cult-like, technocratic “religion of humanity.” The new social order he imagined was deeply conservative and hierarchical, a kind of a caste system with every level of society obliged to reconcile itself with its “scientifically” allotted place. Comte imagined himself at the pinnacle of society, taking the title of “Great Priest of Humanity.” The moral and intellectual anarchy he decried would be resolved through the rule of sociologists who would eliminate the need for unnecessary and divisive democratic dialogue. Social order “must ever be incompatible with a perpetual discussion of the foundations of society” (Comte, 1830/1975).

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German philosopher and economist. In 1848 he and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) co-authored the Communist Manifesto. This book is one of the most influential political manuscripts in history. It also presents in a highly condensed form Marx’s theory of society, which differed from what Comte proposed. Whereas Comte viewed the goal of sociology as recreating a unified, post-feudal spiritual order that would help to institutionalize a new era of political and social stability, Marx developed a critical analysis of capitalism that saw the material or economic basis of inequality and power relations as the cause of social instability and conflict. The focus of sociology, or what Marx called historical materialism (the “materialist conception of history”), should be the “ruthless critique of everything existing,” as he said in a letter to his friend Arnold Ruge (1802-1880). In this way the goal of sociology would not simply be to scientifically analyze or objectively describe society, but to use a rigorous scientific analysis as a basis to change it. This framework became the foundation of contemporary critical sociology.

Although Marx did not call his analysis “sociology,” his sociological innovation was to provide a social analysis of the economic system. Whereas Adam Smith (1723–1790) and the political economists of the 19th century tried to explain the economic laws of supply and demand solely as a market mechanism (similar to the abstract discussions of stock market indices and investment returns in the business pages of newspapers today), Marx’s analysis showed the social relationships that had created the market system, and the social repercussions of their operation. As such, his analysis of modern society was not static or simply descriptive. He was able to put his finger on the underlying dynamism and continuous change that characterized capitalist society.

Marx was also able to create an effective basis for critical sociology in that what he aimed for in his analysis was, as he put it in another letter to Arnold Ruge, “the self-clarification of the struggles and wishes of the age.” While he took a clear and principled value position in his critique, he did not do so dogmatically, based on an arbitrary moral position of what he personally thought was good and bad. He felt, rather, that a critical social theory must engage in clarifying and supporting the issues of social justice that were inherent within the existing struggles and wishes of the age. In his own work, he endeavoured to show how the variety of specific work actions, strikes, and revolts by workers in different occupations — for better pay, safer working conditions, shorter hours, the right to unionize, etc. — contained the seeds for a vision of universal equality, collective justice, and ultimately the ideal of a classless society.

Harriet Martineau (1802–1876) was one of the first women sociologists in the 19th century. There are a number of other women who might compete with her for the title of the first woman sociologist, such as Catherine Macaulay, Mary Wollstonecraft, Flora Tristan, and Beatrice Webb, but Martineau’s specifically sociological credentials are strong. She was for a long time known principally for her English translation of Comte’s Course in Positive Philosophy. Through this popular translation she introduced the concept of sociology as a methodologically rigorous discipline to an English-speaking audience. But she also created a body of her own work in the tradition of the great social reform movements of the 19th century, and introduced a sorely missing woman’s perspective into the discourse on society.

It was a testament to her abilities that after she became impoverished at the age of 24 with the death of her father, brother, and fiancé, she was able to earn her own income as the first woman journalist in Britain to write under her own name. From the age of 12, she suffered from severe hearing loss and was obliged to use a large ear trumpet to converse. She impressed a wide audience with a series of articles on political economy in 1832. In 1834 she left England to engage in two years of study of the new republic of the United States and its emerging institutions: prisons, insane asylums, factories, farms, Southern plantations, universities, hospitals, and churches. On the basis of extensive research, interviews, and observations, she published Society in America and worked with abolitionists on the social reform of slavery (Zeitlin, 1997). She also worked for social reform in the situation of women: the right to vote, have an education, pursue an occupation, and enjoy the same legal rights as men. Together with Florence Nightingale, she worked on the development of public health care, which led to early formulations of the welfare system in Britain (McDonald, 1998).

Émile Durkheim (1858–1917) helped establish sociology as a formal academic discipline by establishing the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895, and by publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method in 1895. He was born to a Jewish family in the Lorraine province of France (one of the two provinces, along with Alsace, that were lost to the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871). With the German occupation of Lorraine, the Jewish community suddenly became subject to sporadic anti-Semitic violence, with the Jews often being blamed for the French defeat and the economic/political instability that followed. Durkheim attributed this strange experience of anti-Semitism and scapegoating to the lack of moral purpose in modern society.

As in Comte’s time, France in the late 19th century was the site of major upheavals and sharp political divisions: the loss of the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune (1871) in which 20,000 workers died, the fall and capture of Emperor Napoleon III (Napoleon I’s nephew), the creation of the Third Republic, and the Dreyfus Affair. This undoubtedly led to the focus in Durkheim’s sociology on themes of moral anarchy, decadence, disunity, and disorganization. For Durkheim, sociology was a scientific but also a “moral calling” and one of the central tasks of the sociologist was to determine “the causes of the general temporary maladjustment being undergone by European societies and remedies which may relieve it” (1897/1951). In this respect, Durkheim represented the sociologist as a kind of medical doctor, studying social pathologies of the moral order and proposing social remedies and cures. He saw healthy societies as stable, while pathological societies experienced a breakdown in social norms between individuals and society. He described this breakdown as a state of normlessness or anomie — a lack of norms that give clear direction and purpose to individual actions. As he put it, anomie was the result of “society’s insufficient presence in individuals” (1897/1951).

Key to Durkheim’s approach was the development of a framework for sociology based on the analysis of social facts and social functions. Social facts are those things like law, custom, morality, religious rites, language, money, business practices, etc. that are defined externally to the individual. Social facts:

For Durkheim, social facts were like the facts of the natural sciences. They could be studied without reference to the subjective experience of individuals. He argued that “social facts must be studied as things, that is, as realities external to the individual” (Durkheim, 1895/1964). Individuals experience them as obligations, duties, and restraints on their behaviour, operating independently of their will. They are hardly noticeable when individuals consent to them but provoke reaction when individuals resist.

Durkheim argued that each of these social facts serve one or more functions within a society. They exist to fulfill a societal need. For example, one function of a society’s laws may be to protect society from violence and punish criminal behaviour, while another is to create collective standards of behaviour that people believe in and identify with. Laws create a basis for social solidarity and order. In this manner, each identifiable social fact could be analyzed with regard to its specific function in a society. Like a body in which each organ (heart, liver, brain, etc.) serves a particular function in maintaining the body’s life processes, a healthy society depends on particular functions or needs being met. Durkheim’s insights into society often revealed that social practices, like the worshipping of totem animals in his study of Australian Aboriginal religions, had social functions quite at variance with what practitioners consciously believed they were doing. The honouring of totemic animals through rites and privations functioned to create social solidarity and cohesion for tribes whose lives were otherwise dispersed through the activities of hunting and gathering in a sparse environment.

Durkheim was very influential in defining the subject matter of the new discipline of sociology. For Durkheim, sociology was not about just any phenomena to do with the life of human beings, but only those phenomena which pertained exclusively to a social level of analysis. It was not about the biological or psychological dynamics of human life, for example, but about the external social facts through which the lives of individuals were constrained. Moreover, the dimension of human experience described by social facts had to be explained in its own terms. It could not be explained by biological drives or psychological characteristics of individuals. It was a dimension of reality sui generis (of its own kind, unique in its characteristics). It could not be explained by, or reduced to, its individual components without missing its most important features. As Durkheim put it, “a social fact can only be explained by another social fact” (Durkheim, 1895/1964).

This is the framework of Durkheim’s famous study of suicide. In Suicide: A Study in Sociology (1897/1997), Durkheim attempted to demonstrate the effectiveness of his rules of social research by examining suicide statistics in different police districts. Suicide is perhaps the most personal and most individual of all acts. Its motives would seem to be absolutely unique to the individual and to individual psychopathology. However, what Durkheim observed was that statistical rates of suicide remained fairly constant, year by year and region by region. Moreover, there was no correlation between rates of suicide and rates of psychopathology. Suicide rates did vary, however, according to the social context of the suicides. For example, suicide rates varied according to the religious affiliation of suicides. Protestants had higher rates of suicide than Catholics, even though both religions equally condemn suicide. In some jurisdictions Protestants killed themselves 300% more often than Catholics. Durkheim argued that the key factor that explained the difference in suicide rates (i.e., the statistical rates, not the purely individual motives for the suicides) were the different degrees of social integration of the different religious communities, measured by the degree of authority religious beliefs hold over individuals, and the amount of collective ritual observance and mutual involvement individuals engage in in religious practice. A social fact — suicide rates — was explained by another social fact — degree of social integration.

The key social function of religion was to integrate individuals by linking them to a common external doctrine and to a greater spiritual reality outside of themselves. Religion created moral communities. In this regard, he observed that the degree of authority that religious beliefs held over Catholics was much stronger than for Protestants, who from the time of Luther had been taught to take a critical attitude toward formal doctrine. Protestants were more free to interpret religious belief and in a sense were were more individually responsible for supervising and maintaining their own religious practice. Moreover, in Catholicism the ritual practice of the sacraments, such as confession and taking communion, remained intact, whereas in Protestantism ritual was reduced to a minimum. Participation in the choreographed rituals of religious life created a highly visible, public focus for religious observance, forging a link between private thought and public belief. Because Protestants had to be more individualistic and self-reliant in their religious practice, they were not subject to the strict discipline and external constraints of Catholics. They were less integrated into their communities and more thrown back on their own resources. They were more prone to what Durkheim termed egoistic suicide: suicide which results from the individual ego having to depend on itself for self-regulation (and failing) in the absence of strong social bonds tying it to a community.

Durkheim’s study was unique and insightful because he did not try to explain suicide rates in terms of individual psychopathology. Instead, he regarded the regularity of the suicide rates as a social fact, implying “the existence of collective tendencies exterior to the individual” (Durkheim, 1897/1997), and explained their variation with respect to another social fact: social integration. He wrote, “Suicide varies inversely with the degree of integration of the social groups of which the individual forms a part” (Durkheim, 1897/1997).

Contemporary research into suicide in Canada shows that suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people aged 15 to 34 (behind death by accident) (Navaneelan, 2012). The greatest increase in suicide since the 1960s has been in the age 15-19 age group, increasing by 4.5 times for males and by 3 times for females. In 2009, 23% of deaths among adolescents aged 15-19 were caused by suicide, up from 9% in 1974, (although this difference in percentage is because the rate of suicide remained fairly constant between 1974 and 2009, while death due to accidental causes has declined markedly). On the other hand, married people are the least likely group to commit suicide. Single, never-married people are 3.3 times more likely to commit suicide than married people, followed by widowed and divorced individuals respectively. How do sociologists explain this?

It is clear that adolescence and early adulthood is a period in which social ties to family and society are strained. It is often a confusing period in which teenagers break away from their childhood roles in the family group and establish their independence. Youth unemployment is higher than for other age groups and, since the 1960s, there has been a large increase in divorces and single parent families. These factors tend to decrease the quantity and the intensity of ties to society. Married people on the other hand have both strong affective affinities with their marriage partners and strong social expectations placed on them, especially if they have families: their roles are clear and the norms which guide them are well-defined. According to Durkheim’s proposition, suicide rates vary inversely with the degree of integration of social groups. Adolescents are less integrated into society, which puts them at a higher risk for suicide than married people who are more integrated. It is interesting that the highest rates of suicide in Canada are for adults in midlife, aged 40-59. Midlife is also a time noted for crises of identity, but perhaps more significantly, as Navaneelan (2012) argues, suicide in this age group results from the change in marital status as people try to cope with the transition from married to divorced and widowed.

Prominent sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) established a sociology department in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich in 1919. Weber wrote on many topics related to sociology including political change in Russia, the condition of German farm workers, and the history of world religions. He was also a prominent public figure, playing an important role in the German peace delegation in Versailles and in drafting the ill-fated German (Weimar) constitution following the defeat of Germany in World War I.

Weber also made a major contribution to the methodology of sociological research. Along with the philosophers Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911) and Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936), Weber believed that it was difficult if not impossible to apply natural science methods to accurately predict the behaviour of groups as positivist sociology hoped to do. They argued that the influence of culture on human behaviour had to be taken into account. What was distinct about human behaviour was that it is essentially meaningful. Human behaviour could not be understood independently of the meanings that individuals attributed to it. A Martian’s analysis of the activities in a skateboard park would be hopelessly confused unless it understood that the skateboarders were motivated by the excitement of taking risks and the pleasure in developing skills. This insight into the meaningful nature of human behaviour even applied to the sociologists themselves, who, they believed, should be aware of how their own cultural biases could influence their research. To deal with this problem, Weber and Dilthey introduced the concept of Verstehen, a German word that means to understand from a subject’s point of view. In seeking Verstehen, outside observers of a social world — an entire culture or a small setting — attempt to understand it empathetically from an insider’s point of view.

In his essay “The Methodological Foundations of Sociology,” Weber described sociology as “a science which attempts the interpretive understanding of social action in order to arrive at a causal explanation of its course and effects” (Weber, 1922). In this way he delimited the field that sociology studies in a manner almost opposite to that of Émile Durkheim. Rather than defining sociology as the study of the unique dimension of external social facts, sociology was concerned with social action: actions to which individuals attach subjective meanings. “Action is social in so far as, by virtue of the subjective meaning attached to it by the acting individual (or individuals), it takes account of the behaviour of others and is thereby oriented in its course” (Weber, 1922). The actions of the young skateboarders can be explained because they hold the experienced boarders in esteem and attempt to emulate their skills, even if it means scraping their bodies on hard concrete from time to time. Weber and other like-minded sociologists founded interpretive sociology whereby social researchers strive to find systematic means to interpret and describe the subjective meanings behind social processes, cultural norms, and societal values. This approach led to research methods like ethnography, participant observation, and phenomenological analysis. Their aim was not to generalize or predict (as in positivistic social science), but to systematically gain an in-depth understanding of social worlds. The natural sciences may be precise, but from the interpretive sociology point of view their methods confine them to study only the external characteristics of things.

Georg Simmel (1858–1918) was one of the founding fathers of sociology, although his place in the discipline is not always recognized. In part, this oversight may be explained by the fact that Simmel was a Jewish scholar in Germany at the turn of 20th century and, until 1914, he was unable to attain a proper position as a professor due to anti-Semitism. Despite the brilliance of his sociological insights, the quantity of his publications, and the popularity of his public lectures as Privatdozent at the University of Berlin, his lack of a regular academic position prevented him from having the kind of student following that would create a legacy around his ideas. It might also be explained by some of the unconventional and varied topics that he wrote on: the structure of flirting, the sociology of adventure, the importance of secrecy, the patterns of fashion, the social significance of money, etc. He was generally seen at the time as not having a systematic or integrated theory of society. However, his insights into how social forms emerge at the micro-level of interaction and how they relate to macro-level phenomena remain valuable in contemporary sociology.

Simmel’s sociology focused on the key question, “How is society possible?” His answer led him to develop what he called formal sociology, or the sociology of social forms. In his essay “The Problem of Sociology,” Simmel reaches a strange conclusion for a sociologist: “There is no such thing as society ‘as such.’” “Society” is just the name we give to the “extraordinary multitude and variety of interactions [that] operate at any one moment” (Simmel, 1908/1971). This is a basic insight of micro-sociology. However useful it is to talk about macro-level phenomena like capitalism, the moral order, or rationalization, in the end what these phenomena refer to is a multitude of ongoing, unfinished processes of interaction between specific individuals. Nevertheless, the phenomena of social life do have recognizable forms, and the forms do guide the behaviour of individuals in a regularized way. A bureaucracy is a form of social interaction that persists from day to day. One does not come into work one morning to discover that the rules, job descriptions, paperwork, and hierarchical order of the bureaucracy have disappeared. Simmel’s questions were: How do the forms of social life persist? How did they emerge in the first place? What happens when they get fixed and permanent?

Simmel’s focus on how social forms emerge became very important for micro-sociology, symbolic interactionism, and the studies of hotel lobbies, cigarette girls, and street-corner societies, etc. popularized by the Chicago School in the mid-20th century. His analysis of the creation of new social forms was particularly tuned in to capturing the fragmentary everyday experience of modern social life that was bound up with the unprecedented nature and scale of the modern city. In his lifetime, the city of Berlin where he lived and taught for most of his career expanded massively after the unification of Germany in the 1870s and, by 1900, became a major European metropolis of 4 million people. The development of a metropolis created a fundamentally new human experience. The inventiveness of people in creating new forms of interaction in response became a rich source of sociological investigation.

Sociologists study social events, interactions, and patterns. They then develop theories to explain why these occur and what can result from them. In sociology, a theory is a way to explain different aspects of social interactions and create testable propositions about society (Allan, 2006). For example, Durkheim’s proposition, that differences in suicide rate can be explained by differences in the degree of social integration in different communities, is a theory.

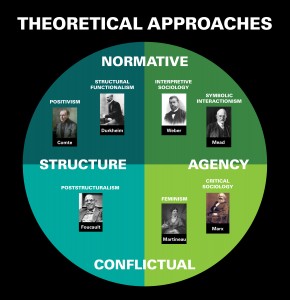

As this brief survey of the history of sociology suggests, there is considerable diversity in the theoretical approaches sociology takes to studying society. Sociology is a multi-perspectival science: a number of distinct perspectives or paradigms offer competing explanations of social phenomena. Paradigms are philosophical and theoretical frameworks used within a discipline to formulate theories, generalizations, and the research performed in support of them. They refer to the underlying organizing principles that tie different constellations of concepts, theories, and ways of formulating problems together (Drengson, 1983). Talcott Parsons’ reformulation of Durkheim’s and others work as structural functionalism in the 1950s is an example of a paradigm because it provided a general model of analysis suited to an unlimited number of research topics. Parsons proposed that any identifiable social structure (e.g., roles, families, religions, or states) could be explained by the particular function it performed in maintaining the operation of society as a whole. Critical sociology and symbolic interactionism are two other sociological paradigms which formulate the explanatory framework and research problem differently.

The variety of paradigms and methodologies makes for a rich and useful dialogue among sociologists. It is also sometimes confusing for students who expect that sociology will have a unitary scientific approach like that of the natural sciences. However, the key point is that the subject matter of sociology is fundamentally different from that of the natural sciences. The existence of multiple approaches to the topic of society and social relationships makes sense given the nature of the subject matter of sociology. The “contents” of a society are never simply a set of objective qualities like the chemical composition of gases or the forces operating on celestial spheres. For the purposes of analysis, the contents of society can sometimes be viewed in this way, as in the positivist perspective, but in reality, they are imbued with social meanings, historical contexts, political struggles, and human agency.

This makes social life a complex, moving target for researchers to study, and the outcome of the research will be different depending on where and with what assumptions the researcher begins. Even the elementary division of experience into an interior world, which is “subjective,” and an exterior world, which is “objective,” varies historically, cross-culturally, and sometimes moment by moment in an individual’s life. From the phenomenological perspective in sociology, this elementary division, which forms the starting point and basis of the “hard” or “objective” sciences, is in fact usefully understood as a social accomplishment sustained through social interactions. We actively divide the flow of impressions through our consciousness into socially recognized categories of subjective and objective, and we do so by learning and following social norms and rules. The division between subjective impressions and objective facts is natural and necessary only in the sense that it has become what Schutz (1962) called the “natural attitude” for people in modern society. Therefore, this division performs an integral function in organizing modern social and institutional life on an ongoing basis. We assume that the others we interact with view the world through the natural attitude. Confusion ensues when we or they do not. Other forms of society have been based on different modes of being in the world.

Despite the differences that divide sociology into multiple perspectives and methodologies, its unifying aspect is the systematic and rigorous nature of its social inquiry. If the distinction between “soft” and “hard” sciences is useful at all, it refers to the degree of rigour and systematic observation involved in the conduct of research rather than the division between the social and the natural sciences per se. Sociology is based on the scientific research tradition which emphasizes two key components: empirical observation and the logical construction of theories and propositions. Science is understood here in the broad sense to mean the use of reasoned argument, the ability to see general patterns in particular incidences, and the reliance on evidence from systematic observation of social reality. However, as noted above, the outcome of sociological research will differ depending on the initial assumptions or perspective of the researcher. Each of the blind men studying the elephant in the illustration above are capable of producing an empirically true and logically consistent account of the elephant, albeit limited, which will differ from the accounts produced by the others. While the analogy that society is like an elephant is tenuous at best, it does exemplify the way that different schools of sociology can explain the same factual reality in different ways

Within this general scientific framework, therefore, sociology is broken into the same divisions that separate the forms of modern knowledge more generally. As Jürgen Habermas (1972) describes, by the time of the Enlightenment in the 18th century, the unified perspective of Christendom had broken into three distinct spheres of knowledge: the natural sciences, hermeneutics (or the interpretive sciences like literature, philosophy, and history), and critique. In many ways the three spheres of knowledge are at odds with one another, but each serves an important human interest or purpose. The natural sciences are oriented to developing a technical knowledge useful for controlling and manipulating the natural world to serve human needs. Hermeneutics is oriented to developing a humanistic knowledge useful for determining the meaning of texts, ideas, and human practices in order to create the conditions for greater mutual understanding. Critique is oriented to developing practical knowledge and forms of collective action that are useful for challenging entrenched power relations in order to enable human emancipation and freedoms.

Sociology is similarly divided into three types of sociological knowledge, each with its own strengths, limitations, and practical purposes: positivist sociology focuses on generating types of knowledge useful for controlling or administering social life; interpretive sociology on types of knowledge useful for promoting greater mutual understanding and consensus among members of society, and critical sociology on types of knowledge useful for changing and improving the world, for emancipating people from conditions of servitude. Within these three types of sociological knowledge, we will discuss five paradigms of sociological thinking: quantitative sociology, structural functionalism, historical materialism, feminism, and symbolic interactionism.

The positivist perspective in sociology — introduced above with regard to the pioneers of the discipline, August Comte and Émile Durkheim — is most closely aligned with the forms of knowledge associated with the natural sciences. The emphasis is on empirical observation and measurement (i.e., observation through the senses), value neutrality or objectivity, and the search for law-like statements about the social world (analogous to Newton’s laws of gravity for the natural world). Since mathematics and statistical operations are the main forms of logical demonstration in the natural scientific explanation, positivism relies on translating human phenomena into quantifiable units of measurement. It regards the social world as an objective or “positive” reality, in no essential respects different from the natural world. Positivism is oriented to developing a knowledge useful for controlling or administering social life, which explains its ties to the projects of social engineering going back to Comte’s original vision for sociology. Two forms of positivism have been dominant in sociology since the 1940s: quantitative sociology and structural functionalism.

In contemporary sociology, positivism is based on four main “rules” that define what constitutes valid knowledge and what types of questions may be reasonably asked (Bryant, 1985):

Much of what is referred to today as quantitative sociology fits within this paradigm of positivism. Quantitative sociology uses statistical methods such as surveys with large numbers of participants to quantify relationships between social variables. In line with the “unity of the scientific method” rule, quantitative sociologists argue that the elements of human life can be measured and quantified — described in numerical terms — in essentially the same way that natural scientists measure and quantify the natural world in physics, biology, or chemistry. Researchers analyze this data using statistical techniques to see if they can uncover patterns or “laws” of human behaviour. Law-like statements concerning relationships between variables are often posed in the form of statistical relationships or multiple linear regression formulas; these measure and quantify the degree of influence different causal or independent variables have on a particular outcome or dependent variable. (Independent and dependent variables will be discussed in Chapter 2). For example, the degree of religiosity of an individual in Canada, measured by the frequency of church attendance or religious practice, can be predicted by a combination of different independent variables such as age, gender, income, immigrant status, and region (Bibby, 2012). This approach is value neutral for two reasons: firstly because the quantified data is the product of methods of systematic empirical observation that seek to minimize researcher bias, and secondly because “values” per se are human dispositions towards what “should be” and therefore cannot be observed like other objects or processes in the world. Quantitative sociologists might be able to survey what people say their values are, but they cannot determine through quantitative means what is valuable or what should be.

Structural Functionalism also falls within the positivist tradition in sociology due to Durkheim’s early efforts to describe the subject matter of sociology in terms of objective social facts — “social facts must be studied as things, that is, as realities external to the individual” (Durkheim, 1895/1997) — and to explain them in terms of their social functions.

Following Durkheim’s insight, structural functionalism therefore sees society as composed of structures — regular patterns of behaviour and organized social arrangements that persist through time (e.g., like the institutions of the family or the occupational structure) — and the functions they serve: the biological and social needs of individuals who make up that society. In this respect, society is like a body that relies on different organs to perform crucial functions. He argued that just as the various organs in the body work together to keep the entire system functioning and regulated, the various parts of society work together to keep the entire society functioning and regulated. By “parts of society,” Spencer was referring to such social institutions as the economy, political systems, health care, education, media, and religion.

According to structural functionalism, society is composed of different social structures that perform specific functions to maintain the operation of society as a whole. Structures are simply regular, observable patterns of behaviour or organized social arrangements that persist through time. The institutional structures that define roles and interactions in the family, workplace, or church, etc. are structures. Functions refer to how the various needs of a society (i.e., for properly socialized children, for the distribution of food and resources, or for a unified belief system, etc.) are satisfied. Different societies have the same basic functional requirements, but they meet them using different configurations of social structure (i.e., different types of kinship system, economy, or religious practice). Thus, society is seen as a system not unlike the human body or an automobile engine.

In fact the English philosopher and biologist Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) likened society to a human body. Each structure of the system performs a specific function to maintain the orderly operation of the whole (Spencer, 1898). When they do not perform their functions properly, the system as a whole is threatened. The heart pumps the blood, the vascular system transports the blood, the metabolic system transforms the blood into proteins needed for cellular processes, etc. When the arteries in the heart get blocked, they no longer perform their function. The heart fails, and the system as a whole collapses. In the same way, the family structure functions to socialize new members of society (i.e., children), the economic structure functions to adapt to the environment and distribute resources, the religious structure functions to provide common beliefs to unify society, etc. Each structure of society provides a specific and necessary function to ensure the ongoing maintenance of the whole. However, if the family fails to effectively socialize children, or the economic system fails to distribute resources equitably, or religion fails to provide a credible belief system, repercussions are felt throughout the system. The other structures have to adapt, causing further repercussions. With respect to a system, when one structure changes, the others change as well. Spencer continued the analogy to the body by pointing out that societies evolve just as the bodies of humans and other animals do (Maryanski and Turner, 1992).

According to American sociologist Talcott Parsons (1881–1955), in a healthy society, all of these parts work together to produce a stable state called dynamic equilibrium (Parsons, 1961). Parsons was a key figure in systematizing Durkheim’s views in the 1940s and 1950s. He argued that a sociological approach to social phenomena must emphasize the systematic nature of society at all levels of social existence: the relation of definable “structures” to their “functions” in relation to the needs or “maintenance” of the system. His AGIL schema provided a useful analytical grid for sociological theory in which an individual, an institution, or an entire society could be seen as a system composed of structures that satisfied four primary functions:

So for example, the social system as a whole relied on the economy to distribute goods and services as its means of adaptation to the natural environment; on the political system to make decisions as its means of goal attainment; on roles and norms to regulate social behaviour as its means of social integration; and on cultural institutions to reproduce common values as its means of latent pattern maintenance. Following Durkheim, he argued that these explanations of social functions had to be made at the macro-level of systems and not at the micro-level of the specific wants and needs of individuals. In a system, there is an interrelation of component parts where a change in one component affects the others regardless of the perspectives of individuals.

Another noted structural functionalist, Robert Merton (1910–2003), pointed out that social processes can have more than one function. Manifest functions are the consequences of a social process that are sought or anticipated, while latent functions are the unsought consequences of a social process. A manifest function of college education, for example, includes gaining knowledge, preparing for a career, and finding a good job that utilizes that education. Latent functions of your college years include meeting new people, participating in extracurricular activities, or even finding a spouse or partner. Another latent function of education is creating a hierarchy of employment based on the level of education attained. Latent functions can be beneficial, neutral, or harmful. Social processes that have undesirable consequences for the operation of society are called dysfunctions. In education, examples of dysfunction include getting bad grades, truancy, dropping out, not graduating, and not finding suitable employment.

The main criticisms of both quantitative sociology and structural functionalism have to do with whether social phenomena can truly be studied like the natural phenomena of the physical sciences. Critics challenge the way in which social phenomena are regarded as objective social facts. On one hand, interpretive sociologists suggest that the quantification of variables in quantitative sociology reduces the rich complexity and ambiguity of social life to an abstract set of numbers and statistical relationships that cannot capture the meaning it holds for individuals. Measuring someone’s depth of religious belief or “religiosity” by the number of times they attend church in a week explains very little about the religious experience itself. Similarly, interpretive sociology argues that structural functionalism, with its emphasis on macro-level systems of structures and functions tends to reduce the individual to the status of a sociological “dupe,” assuming pre-assigned roles and functions without any individual agency or capacity for self-creation.

On the other hand, critical sociologists challenge the conservative tendencies of quantitative sociology and structural functionalism. Both types of positivist analysis represent themselves as being objective, or value-neutral, whereas critical sociology notes that the context in which they are applied is always defined by relationships of power and struggles for social justice. In this sense sociology cannot be neutral or purely objective. The context of social science is never neutral. However, both types of positivism also have conservative assumptions built into their basic approach to social facts. The focus in quantitative sociology on observable facts and law-like statements presents an ahistorical and deterministic picture of the world that cannot account for the underlying historical dynamics of power relationships and class, gender, or other struggles. One can empirically observe the trees but not see the forest so to speak.

Similarly, the focus on the needs and the smooth functioning of social systems in structural functionalism supports a conservative viewpoint because it relies on an essentially static model of society. The functions of each structure are understood in terms of the needs of the social system as it exists at a particular moment in time. Each individual has to fit the function or role designated for them. Change is not only dysfunctional or pathological, because it throws the whole system into disarray, it also is very difficult to understand why change occurs at all if society is functioning as a system. Therefore, structural functionalism has a strong conservative tendency, which is illustrated by some of its more controversial arguments. For example, Davis and Moore (1944) argued that inequality in society is good (or necessary) because it functions as an incentive for people to work harder. Talcott Parsons (1954) argued that the gender division of labour in the nuclear family between the husband/breadwinner and wife/housekeeper is good (or necessary) because the family will function coherently only if each role is clearly demarcated. In both cases, the order of the system is not questioned, and the historical sources of inequality are not analysed. Inequality in fact performs a useful function. Critical sociology challenges both the social injustice and practical consequences of social inequality. In particular, social equilibrium and function must be scrutinized closely to see whose interests they serve and whose interests they suppress.